Recent major market reforms in China have signalled an imminent end to the era of feed-in tariffs for solar and wind. Carrie Xiao assesses the impact of the policy as developers rush to complete projects before the rules change and a spike in demand pushes module prices up.

Since March, a rush to install projects and a brutal fight to secure modules as prices soar has intensified across the entire PV industry chain in China.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

Or continue reading this article for free

Many PV projects need to be connected to the grid before the 31 May to secure favourable power prices and guarantees. Missing this deadline could mean losing the final window for the power prices secured under “Policy No.136”, which despite its innocuous-sounding name embodies a seismic shift in the route to market for new PV and other renewables projects in China.

Policy No.136 is the industry’s colloquial term for a policy jointly issued by two ministries in China. On 9 February 2025, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the National Energy Administration (NEA) jointly released the “Notice on deepening the market-oriented reform of feed-in tariffs for new energy and promoting high-quality development of new energy” (NDRC Price [2025] No. 136).

The policy sets a time threshold. Wind, PV and solar-thermal projects that are connected to the grid before 31 May 2025 can enjoy guaranteed purchase prices. Starting from 1 June, new projects will fully enter a “double non-guaranteed” market-based bidding mechanism, where both the scale and price of power generation are subject to market competition.

With the release and implementation of Policy No. 136, China’s new energy projects now have to contend with entirely new rules of the game, marking the end of the era of feed-in tariffs for wind and solar power.

So, what are the main contents of this market-oriented reform of renewable feed-in tariffs? What benefits will the reform bring? And how will the Policy No. 136 impact the market? This article will detail the impact of China’s new round of new energy policies on the PV industry.

| Milestone | Main impacts of policy on PV and other ‘new energy’ generators |

| Before 31 May | Projects that can be connected to the grid will still enjoy the guaranteed feed-in tariff policy. |

| Starting 1 June | All power generated from new projects will enter the market for trading. The scale and price of power connected to the grid, and the investment payback period are all uncertain. |

The underlying logic of the market-oriented reform of new energy feed-in tariffs

An NEA spokesperson stated in an interview that the main contents of this reform include three aspects: promoting the formation of new energy feed-in tariffs that are entirely determined by the market; establishing a price settlement mechanism that supports the sustainable development of new energy; and implementing differentiated policies for existing and new projects. These three aspects are interconnected, forming a relatively rigorous and comprehensive reform system.

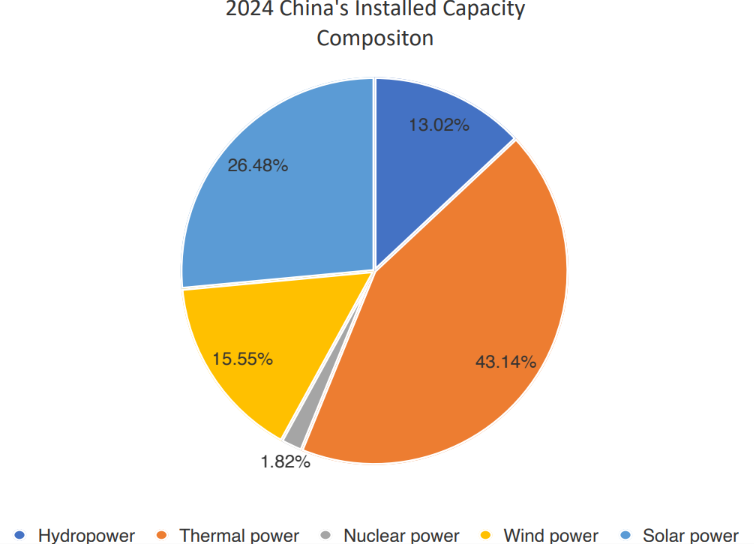

According to the national power industry statistics released by the National Energy Administration for 2024, China’s cumulative installed capacity reached approximately 3.35 billion kilowatts, representing a year-on-year increase of 14.6%. Thermal power accounted for only 1.44 billion kilowatts, representing only 43.1% of the total.

‘New energy’ is a term that has specific characteristics in China. According to the “Industrial Structure Adjustment Guidance Catalog (2024)”, new energy includes wind power, PV, marine energy, geothermal energy, biomass energy and hydrogen energy. Traditional energy refers to coal, oil and hydropower (including conventional hydropower and pumped storage). Based on this definition, only wind and solar are considered new energy in the capacity composition. However, many countries categorise wind, solar, nuclear and hydropower together as clean or green energy.

New energy accounted for 42.03% of China’s installed capacity composition in 2024, and the new energy feed-in tariff market has become an indispensable part of the national market, which is very important for the health and stability of the national power pricing market.

Yu Pengkun, an expert columnist at Chinese news website Guancha.cn, stated: “Since NDRC issued the notice, the feed-in tariff of coal-fired power has been fully marketised, and a preliminary unified national market has been achieved.

“In contrast, the new energy feed-in tariff market in 2024 is still strictly divided by province, with some provinces even having internal ‘divisions’. For example, the Inner Mongolia grid, due to its large east-west span, is divided into the Eastern Inner Mongolia grid and the Western Inner Mongolia grid, with different new energy trading methods and prices. Therefore, the national power market is not so consistent in pricing mechanism, which needs improvement.”

Currently, the main methods of new energy trading in China include medium- and long-term trading, green power trading and spot trading. Medium- and long-term trading mainly refers to companies supplying power to the grid as required within a specified period and receiving payment according to the contract. Green power trading refers to companies supplying power to designated demanders and receiving payment according to established rules.

To support the development of new energy, the rules for green power trading are more favourable than those of spot trading. Spot trading prices are determined in real time based on demand, and companies can supply power to the grid at any time.

All three power trading methods are market-oriented. Therefore, Policy No.136 emphasises “promoting the formation of new energy feed-in tariff by the market”, with a focus on “comprehensive marketisation”.

Yu Pengkun explained that, from this perspective, there are two main issues in the current new energy power trading market. First, the proportion of medium- and long-term trading contracts is excessively high. The proportion of medium- and long-term contracts exceeds 80%, which is significantly higher than that of green power trading, and with even fewer new energy companies participating in spot trading. Second, the main pricing policies in various provinces are diverse and inconsistent with the direction of a unified national market. The primary pricing strategies in different regions can be categorised as = “threshold + fixed price”, “peak-valley pricing”, “encouraging spot trading”, or combinations of these three models.

In addition to variations in local policies, the acceptance of PV power also varies. Currently, the price of new energy power in China is significantly lower than that of thermal power, yet many new energy companies still have a certain aversion to spot trading.

Yu Pengkun stated: “This is related to the characteristics of new energy, namely randomness, volatility and intermittency. Taking PV power generation as an example, its efficiency is closely related to the intensity of sunlight received by the equipment. Specifically, within a single day, PV power generation efficiency is directly proportional to solar radiation and daylight duration, while it is inversely proportional to factors such as cloud cover and humidity. For a small area like a PV power plant, current weather forecasts cannot accurately predict cloud cover and rainfall, making it difficult to accurately forecast the next day’s power generation; this is the ‘randomness.’”

According to data from the China Meteorological Administration, solar radiation in North China is at its highest in May, June and July. However, the efficiency of PV power generation is higher in March, April, September and October, with power generation in autumn exceeding that of summer. In southern regions, due to the additional impact of rainfall, PV power generation efficiency in June is lower than that in North China. This reflects the “volatility” and “intermittency” of PV power. Numerous practical cases of PV power plants have shown that darkness, rainfall and snowfall will affect power generation.

Yu Pengkun said: “In medium- and long-term trading and green power trading modes, the impact of actual power consumption changes on prices is minimal. However, in spot trading mode, the impact of actual power consumption changes on prices is significant, with off-peak prices generally ranging from 0 to 0.3 times the benchmark price. Industrial powerhouses like Shandong and Zhejiang have even experienced negative prices, meaning that at certain times, power generation companies not only receive no payment but may also incur additional costs.”

He added that, of course, negative and zero prices are highly localised and temporary phenomena, but in spot trading, low prices are the norm during off-peak hours.

Therefore, without a transition period and buffer, directly implementing “comprehensive” marketisation would have a significant impact on the new energy industry. The second key point of Policy No. 136 is to establish a price settlement mechanism that supports the sustainable development of new energy.

With technological advancements and cost reductions, the cost of PV projects is decreasing year by year. If projects with different costs supply power at the same price, it would undoubtedly discourage investors from investing in new projects and technologies and fail to reflect the contributions of older projects to industrial development.

Yu Pengkun continued: “Therefore, the last important aspect of the reform – ’differentiated policies for existing and incremental projects’ – is aimed at addressing this issue. For projects commissioned after 1 June this year, the power price will be determined through market-based bidding. As for existing projects, it is necessary to take into account the actual applicable pricing mechanisms for each project and integrate them with the new policy.

‘Hunger Games’ begin, module prices soar

Policy No. 136 clearly sets 1 June 2025 as the milestone, treating existing and new projects under different rules of the game. Due to the explicit timing, the most immediate and visible impact on the PV industry is reflected in PV equipment prices.

To take advantage of the policy before it ends, module prices have soared. From mid-February to early March, module prices rose from RMB0.67/W (US$0.092/W) to RMB0.72/W (US$0.099/W). During this period, leading companies such as LONGi and Trina Solar raised their ex-factory prices by RMB0.02-0.05/W, with both domestic and international prices rising.

“Driven by the policy, there is a shortage of modules in the market, and agents can’t secure goods even with money. The factory capacity is limited, and there has even been a ‘hunger marketing’ where the highest bidder wins,” agents from several first-tier module companies told PV Tech.

Niu Yanyan, president of LONGi Green’s distributed business in China, told the media that before the Lunar New Year that module manufacturers’ inventory levels were very low. After the policy was announced in mid-February (post-holiday), manufacturers were short of finished products, materials and workers. Affected by market supply and demand and the rush to install, PV module prices have rebounded.

In addition to module price increases, upstream material prices, glass prices, labour costs and construction costs have all risen. Many investors who had previously booked PV projects have started urging for installation, aiming to connect to the grid before 31 May. Some contractors have indicated that the project schedules have been postponed until mid-April.

YC Solar, for example, said that currently, dozens of the company’s projects are in a race against time to make progress before the deadline and rush the construction schedule, and even four distributed PV projects were started simultaneously on the same day.

InfoLink Consulting also analysed the rush to install under the new PV policy in a research report. The agency believes that, affected by domestic policies, the market experienced a rush to install during the policy window period, especially in the distributed market. With a significant increase in product delivery on the distributed market, manufacturers’ order-taking rates have risen noticeably from March to April.

Additionally, under the continuous influence of industry self-discipline, manufacturers have controlled production well from January to March. After the initial inventory sell-off, overseas inventory has

significantly decreased, leading to shortages of some popular models.

Future market direction

After such a frenzied rush to install, how will the market develop? How will China’s PV installations and module prices evolve in the second half of 2025?

He Lei, vice general manager of Shenzhen Xinlei New Energy, expressed concerns about whether the industry can maintain stable development after the installation rush. “The current price increase-driven capacity release has temporarily alleviated supply tension but has planted deeper imbalances for the market—when the policy window period ends, the demand side may face a ‘high dive’, and prices may collapse again,” He Lei said.

Regarding the future market forecast for module prices, LONGi’s Niu Yanyan said that if the market price of PV modules slightly adjusts in the future, it is expected to occur after July.

InfoLink Consulting said that the growth in overseas market demand and domestic industry self-discipline to reduce and control production are the main factors affecting whether module prices can remain stable after the current installation rush.

Wang Bohua, the honorary chairman of the China PV Industry Association, said that in 2025, affected by the management measures for distributed PV power generation, the market-oriented reform of new energy feed-in tariffs, and the time lag between the implementation of these policies and the specific measures introduced by various provinces, the industry will experience some fluctuations, increasing the uncertainty of installation expectations for 2025.

Guojin Securities, on the other hand, holds an optimistic view, stating that the core driving force behind the price increase is the profit-seeking business demands, with the rush to install acting merely as a catalyst. The institution predicts that the demand for PV plants in H2 of 2025 will not experience a “cliff like” decline, and the industry’s prosperity will show a general upward trend despite fluctuations.